By Hilde Perrin, Library Assistant

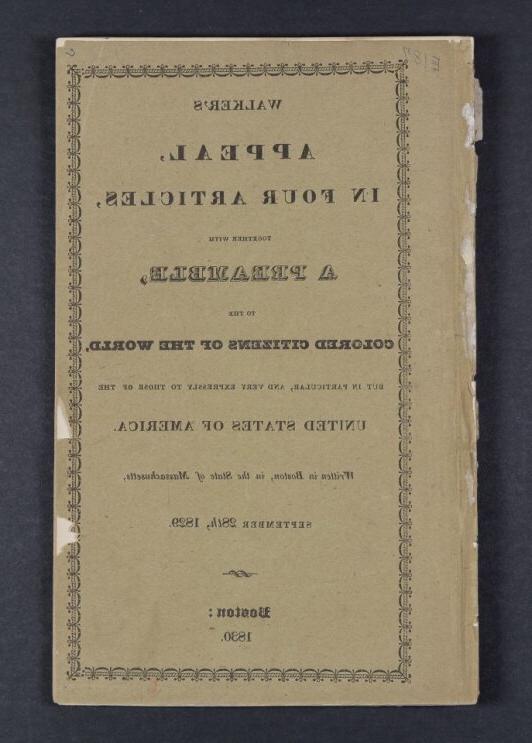

With Black History Month upon us, I wanted to investigate items in our collection related to the Black experience in Massachusetts. One item is a pamphlet written by David Walker, titled “Walker’s appeal in four articles: together with a preamble, to the colored citizens of the world, but in particular, and very expressly to those of the United States of America.” Walker’s pamphlet addresses his fellow Black citizens, encouraging them to work against slavery, and calls attention to the racism in the abolition movement.

Born in North Carolina, David Walker relocated to Boston, where he operated a clothing shop and served as an active member of Boston’s Black community.1 Walker was a founding member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association (MGCA), a Black-led abolitionist organization which argued for equal rights, fighting against slavery and segregation. The MGCA was active in Boston, and later became more broadly known for merging with the New England Anti-Slavery Association in 1833.2 Published in 1830, the abolitionist pamphlet is a powerful piece of writing that exhibits Walker’s and the MGCA’s views on slavery and the need not only for abolition, but for equal rights.

The pamphlet is divided into four parts, covering the consequences of slavery, the religious aspects of slavery, and the problems of the colonization movement, which was active during this period. Walker wastes no time in airing his grievances, calling slavery the “curse to nations”3 that makes his fellow Black Americans the “most degraded, wretched, and abject” beings4. Grounding himself in his Protestant Christian faith, he asserts the evils of slavery and the humanity of African Americans using his language in the pamphlet. Walker repeatedly refers to African Americans as “citizens.” While Black Americans did not legally possess citizenship until after the passage of the 14th amendment in 1868,5 Walker uses the word to emphasize a key point in his argument – the importance of their humanity. “You are men, as well as they”6 he asserts. He further discusses this by citing the bible and calling out white Christians particularly for their lack of equality. Elaborating on the reluctance of white Christians to accept Black Americans as equal in humanity, Walker challenges white readers to support not just the abolition of slavery for their own consciences, but for the equal rights of their fellow humans.

The pamphlet showcases Walker’s education and classical knowledge – providing biblical and classical examples against slavery throughout his argument and writing in dialogue with racist founders like Thomas Jefferson and contemporaries like Henry Clay. Using biblical examples of the Israelites enslavement by the Egyptians, he elaborates that even while they were enslaved, they were treated with more humanity than the enslaved in the 19th century United States.7 Not only does he showcase his education through his writing, he also argues for the importance of education, calling to educated African Americans to enlighten their “ignorant brethren.”8 Walker sees the need for education as connected with the need for freedom and encourages his readers to seek it out for themselves and others.

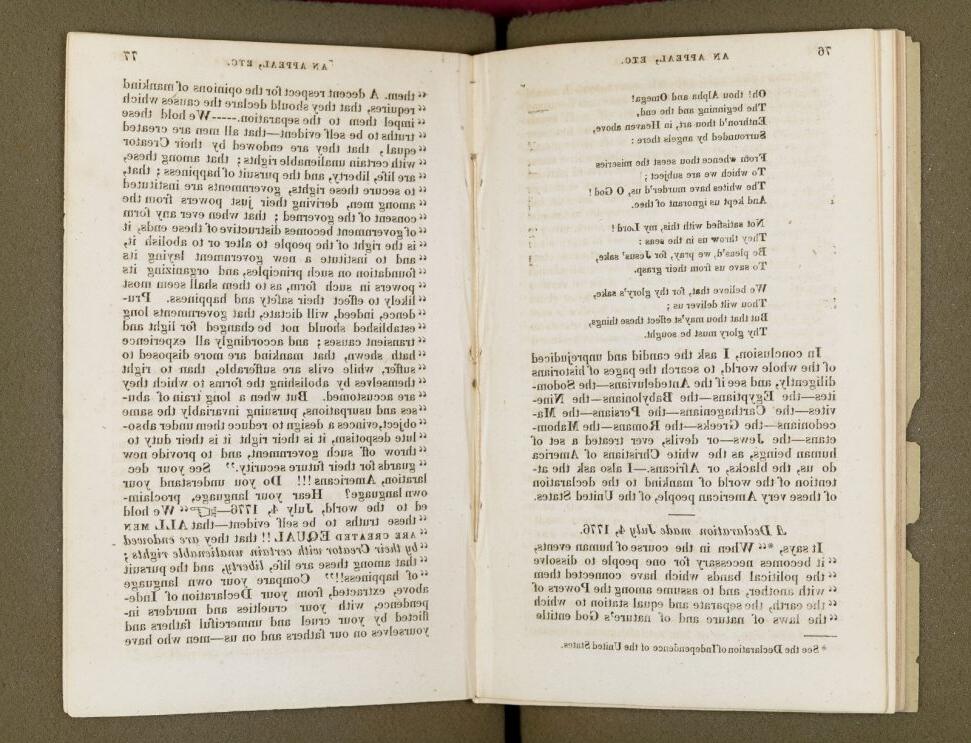

Walker concludes the article by printing an excerpt from the Declaration of Independence, and highlights to readers the hypocrisy of the document, asking “Do you see your declaration, Americans!!!!!! Do you understand your own language?”9 He tasks white Americans with raising the enslaved to the condition of “respectable men,” and further stating that they must “make a national acknowledgement to us for the wrongs they have inflicted.”10 With dramatic use of exclamation points and capital letters, Walker crafts his language to display his anger and to emphasize the importance of his argument. His fiery language reminds us today of the weight of slavery, and the responsibility that comes with perpetuating it, and gives us a glimpse into the Black participation in the abolition movement.11